The Vestry House, dating from the 1830s, stands at the south west corner of the church and is built of brick and stone with tripartite windows. It was perhaps designed by Robert Smirke, who built the rectory at 39 King William Street in 1833-35 (sold in 1921 and subsequently demolished) and whose pupil Henry Roberts designed Fishmongers’ Hall. A 17th century fireplace from Plumbers’ Hall was re-erected in the Vestry House when that was demolished in 1863. The Coroner’s Court met in the Vestry Room in the 1840s. Its cases included drownings at London Bridge, suicides by jumping from the Monument, accidents and deaths from natural causes.

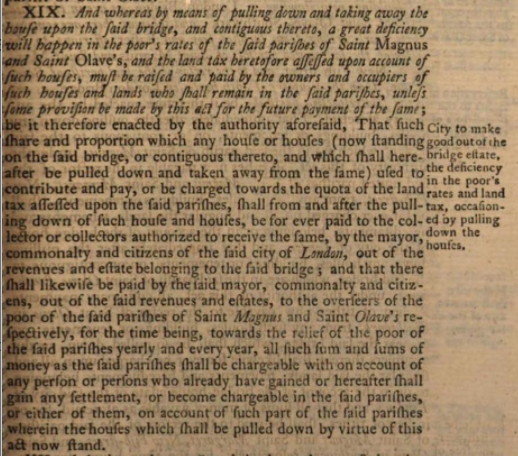

The current Vestry House replaced one built in 1768 by George Dance the Younger. This was constructed following the demolition of the original vestry rooms at the western end of the church, which had been demolished as part of the widening of old London Bridge. A diarist recorded that soldiers were stationed in the Vestry Room during the Gordon Riots in June 1780 to guard the Toll House and Waterworks.

From the early 15th until the 18th century the site was a cloister, used primarily as a graveyard. For example, Henry Crane, citizen and fletcher, requested burial in the cloister of St Magnus Martyr and left 3s 4d to the parish clerks’ brotherhood to pray for his soul in his will of 18 July 1486. In mediaeval times the cloister would also have been used for processional purposes. From the mid-16th century there were properties above the cloister. These were rebuilt in the mid-1640s, the Churchwardens’ accounts recording the use of 11,500 bricks and supervision by the “Master, Wardens and Company of Carpenters who several times viewed and gave judgment touching the scantling of timber and carpenters’ work”. The churchwardens also recorded “that because this parish alloweth Mr Caryl our parson yearly towards his lecture £20 out of the church stock which is not paid him in moneys … he hath his dwelling in part of the new building in the cloister lately built”.

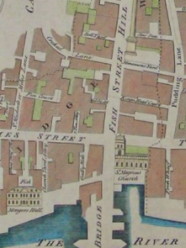

The Vestry House was designed for meetings of the vestry. Local government in the City of London (the ‘Square Mile’) was historically shared between the Corporation of London (the Mayor, Commonalty, and Citizens of the City of London), the Commissioners of Sewers of the City of London (established after the Great Fire), and the vestries of the City parishes. St Magnus is situated in Bridge Ward (now the Ward of Bridge and Bridge Without). From 1603 the parish conducted its business through a Select Vestry of 32 persons selected from the parishioners at large.

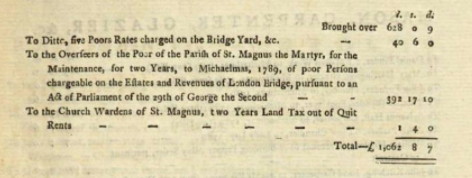

The vestries, comprising rate-paying householders, had a dual ecclesiastical and civil role. They elected the churchwardens and overseers of the poor, maintained the church (including its fabric, ornaments and burial ground), managed charitable funds (for the poor and for sermons) and administered the poor law; levying church and poor rates to meet their expenses, and receiving annual accounts from the churchwardens of receipts and disbursements. From 1837 the City vestries collaborated through the Board of Guardians of the City of London Poor Law Union, created under the Poor Law Amendment Act 1834, but continued to collect their own poor rate until 1907.

There was no school in the three United Parishes, but the church raised funds to assist children attending the combined Bridge, Candlewick and Dowgate Wards School (situated at 13 Swan Lane in the parish of St Martin Orgar until the school merged in 1891 with the Billingsgate and Tower Wards School).

The nature of the role meant that vestry members and even churchwardens were not always members of the Church of England. Churchwardens were elected under Canon 89 of 1603 but did not have to be communicant members of the Church of England until 1964. In 1905 Alderman Sir John Stuart Knill, Bt (1856–1934), a Roman Catholic, was recorded as a member of St Magnus Martyr Vestry. In 1856 the vestry of St Magnus unanimously re-elected a Jewish churchwarden, Henry Levy Keeling (1806-1880, freeman of the City 1842, senior partner of Keeling & Hunt, fruit merchants of Monument Yard and Pudding Lane, and brother-in-law of Abraham Benisch, editor of the Jewish Chronicle), an event that Thomas Slingsby Duncombe (Radical MP for Finsbury) used in a speech in the House of Commons in support of the Oaths Bill for the relief of Her Majesty’s Subjects professing the Jewish religion:-

Mr T. Duncombe said, it was admitted on all sides, that all parties were ashamed of the oath of abjuration, and there was no occasion to discuss that question any longer. It was therefore to be hoped that the country would no longer see 654 gentlemen professing to represent the intelligence of the people, and a large number of high and distinguished persons representing the hereditary wisdom of the nation, solemnly calling upon God that they abjured any allegiance to persons who they knew had long ceased to exist. It appeared, however, that Gentlemen opposite admitted that it was not the family of the Stuarts of whom they were apprehensive, but that they had an insurmountable objection to the house of Rothschild. But the hon. and learned Gentleman (Sir F. Thesiger) who had moved the Amendment had not told the House how he got over the difficulty of the citizens of London having returned a Jew to Parliament. The citizens of London did not participate in the prejudices of the hon. and learned Gentleman, and they had returned a Jew to represent them in Parliament during nine sessions and two Parliaments. It was degrading to the representative of the city, insulting to the citizens of London, and humiliating to the House of Commons that matters should remain as they were. Suppose that 100 Members of the Jewish persuasion were returned by the constituencies of this country, would the House allow matters to continue in their present state? The hon. and learned Gentleman had alluded to the fact that the Lord Mayor of London had attended at St. Paul’s on Thanksgiving-day. He was afraid he should shock the hon. and learned Gentleman much more when he told him that Christian congregations in the city sometimes selected churchwardens of the Jewish persuasion to administer the affairs of a Christian Church. Mr. Keeling, a Gentleman of the Jewish persuasion, had been elected churchwarden for two parishes—St. George, Botolph Lane, and St. Magnus the Martyr—on two or three occasions. He wrote for information on the subject, and received a letter from Mr. Keeling, which he would take leave to read to the House:—

Dear Sir,—The parishes I have represented are St. George, Botolph Lane, and St. Magnus the Martyr, London Bridge; to the latter I was re-elected on Easter Tuesday last. The duty involves the safe guardianship of the church, and properties connected therewith; the proper observance of the service in conformity with existing laws; to levy rates for its support, and, if necessary, to enforce the payment of them; to report to the bishop of the diocese any neglect of duty on the part of the ministers; and the declaration made before the registrars of the bishop to carry out these regulations is framed in so liberal a spirit that it has been most conscientiously subscribed to by me, in company with my Christian colleague, without the least sacrifice of my religious scruples. I may say I have faithfully performed the duties of the office to the satisfaction of the rectors and the parishioners generally.But that was not all. Two or three Sundays ago the Bishop of Lichfield preached a sermon in the church of St. Magnus the Martyr, on behalf of the education of the children of the parish. The Lord Mayor attended there also, and it was of course the duty of the Hebrew churchwarden to receive the bishop with all the honours of the Church. The Bishop left the church without being un-christianised, a subscription was made and Christian education was aided by the exertions of the Jewish churchwarden. He believed that the cause of religion would not suffer very materially if they allowed some few members of the Jewish persuasion to have seats within the walls of the House of Commons. He was glad upon this occasion to see the noble Lord the Member for the City of London come to the rescue. Last year the noble Lord seemed to despond, but he hoped there was now some reason for believing that this question would be settled during the present Session in the other House of Parliament. It must be remembered that an unreformed Parliament had repealed the Test and Corporation Acts, and had conceded Catholic emancipation. He hoped that a reformed Parliament would not perpetuate the last relic of bigotry and intolerance which prevented the admission of Jews into the British Legislature.Question put “That the word proposed to be left out, stand part of the Bill.”

The House divided:—Ayes 159; Noes 110: Majority 49.

Bill passed.

Third reading, House of Commons, 9 June 1856

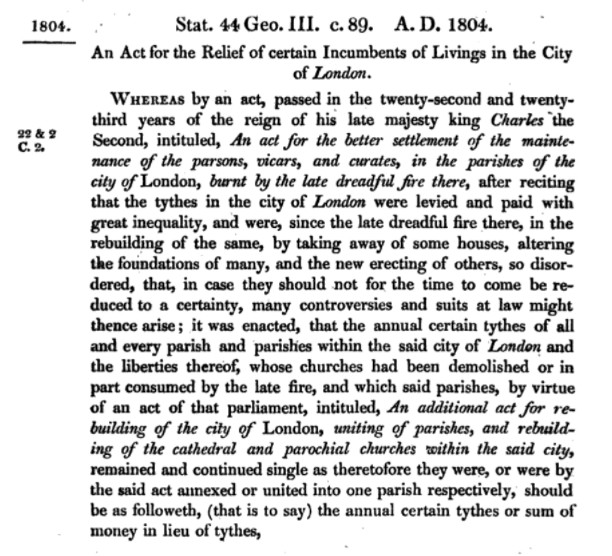

The role of the vestry diminished from the end of the 19th century as powers were transferred to other bodies. The City Parochial Foundation was established in 1891 to administer the charitable endowments of 107 of the City parishes (including the three united parishes of St Magnus the Martyr, St Margaret New Fish Street and St Michael Crooked Lane) under the City of London Parochial Charities Act 1883. The Court of Common Council (the elected body of the Corporation of London) assumed the highway and sanitary powers of the Commissioners of Sewers under the City of London Sewers Act 1897 and responsibility for the poor law under the City of London (Union of Parishes) Act 1907, which created a single civil parish for the City of London:

On and after the appointed day the parishes and places specified in the schedule to this Act (in this Act called “the existing parishes”) shall for all purposes other than ecclesiastical or charitable purposes or purposes of income tax inhabited house duty or land tax be united and shall form one parish to be called “the parish of the city of London” and shall continue to form the City of London Poor Law Union.

As from the appointed day subject to the provisions of this Act the property powers duties and liabilities of the vestry (not being property powers duties or liabilities relating to ecclesiastical affairs or charities) in each of the existing parishes shall be transferred to the Common Council

Section 5 (union of parishes) and Section 13 (transfer of powers of vestry) of the City of London (Union of Parishes) Act 1907

Vestries continued to manage church business until the Parochial Church Councils (Powers) Measure 1921 was made under Church of England Assembly (Powers) Act 1919 and Rules for the Representation of the Laity. This provided for the remaining functions of vestries, apart from the annual election of churchwardens, to be transferred to Parochial Church Councils. The Parochial Church Council of the ecclesiastical parish of St Magnus the Martyr with St Margaret New Fish Street and St Michael Crooked Lane was constituted on 24 April 1922.

Prior to the introduction of civil registration in 1837, only entries of baptisms, marriages and burials in parish registers of the Church of England were accepted as admissible evidence at law. Statistics were compiled from the weekly bills of mortality complied by parish clerks, an ancient office governed by canon law.

The parish clerk was formerly appointed by the incumbent under Canon 91 of 1603 and (until curates and lay readers took on the role from the mid-19th century) assisted the clergyman by leading the people in responses at morning and evening prayer and performing certain duties at baptisms, marriages and burials. The appointment is now made under the Parochial Church Councils (Powers) Measure 1956. The parish clerks of the ancient parishes of London are eligible for election to The Worshipful Company of Parish Clerks.