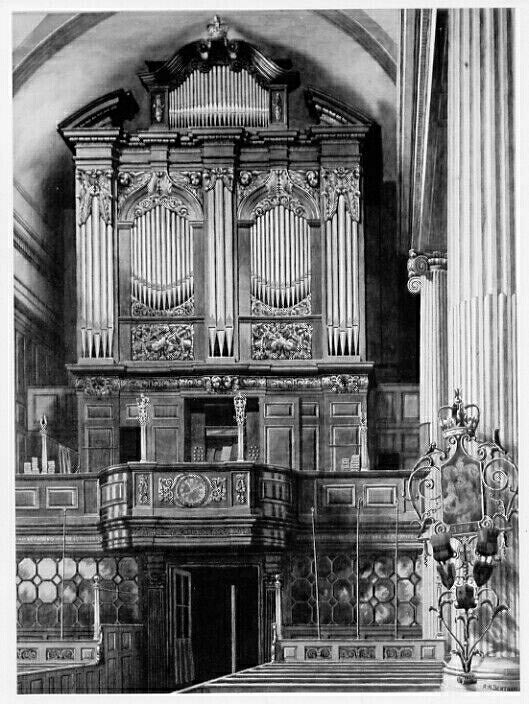

The west end of the nave is dominated by the gallery, organ case and organ, with its double-storeyed array of pipes reaching up to the roof. The organ was the gift of Sir Charles Duncombe. Click on the ‘zoomable’ high resolution still to examine the carving in detail.

Gallery

The early 18th century gallery is supported by two wrought-iron piers and wooden beams in the narthex. Its front has raised panels and pilasters with a moulded plinth and capping; the middle section, projecting into the nave, has carved pilasters flanking a carved panel surrounding the clock. On the gallery front there are four iron standards in the form of Corinthian columns, two supporting mitres and two the crowned monogram A.R. for Queen Anne.

Organ case

The lower part of the oak organ case has raised panels and an entablature; the frieze is carved with acanthus leaves, scallop shells and palm leaves at either end, and two cherub-heads in the middle. The upper part is in two bays with panels richly carved with musical instruments and flowers, arched openings with pierced carving running up to the main entablature, and carved cherub-heads in the spandrels. The bays are flanked by three projecting towers of pipes surmounted by carved acanthus leaves. The whole is surmounted by a continuous entablature, recessed over the bays, with a carved acanthus leaf cornice and broken pediment. Over the middle of the organ there is a secondary pediment in double-ogee form, carried on carved pilasters, enclosing pipes and broken in the centre by a small pedestal surmounted by a gilt crown.

Organ

The organ was built in 1711-12 by Abraham Jordan, assisted by his son of the same name. It was not unusual at the time to build a set of pipes inside a box, called an Eccho organ. This meant that the pipes sounded very muted. Jordan’s idea was to make one side of the box so it could be shut and gradually opened, giving a gradation of sound without adding or subtracting stops. He described it, in an advertisement in the Spectator in February 1712 as “emitting sounds by swelling the notes”. Thus was born the so-called ‘Swell box’, a device which has since become a commonplace feature on organs built around the world.

The Jordans, in their advert in ‘The Spectator’ claimed to have built the organ ‘joynery excepted’. Who exactly helped them build the magnificent case is unclear, but the elegance and the consistently high quality of carving and craftsmanship is remarkable. Two panels featuring instruments are particularly fine and are considered to be examples of the Grinling Gibbons school. It is even possible that Gibbons carved them himself, as he is known to have been working at a nearby church at the time these were made, but we lack conclusive evidence.

Over the course of more than three centuries, the organ has changed and been developed by a succession of some of England’s finest organ-builders. The present instrument has three keyboards or ‘manuals’. We know little about the original 1712 organ upon which John Robinson (organist 1712-62) first played except that, according to the Spectator, it consisted of ‘four setts of keys’. It is highly unlikely that any of these sets of keys were pedals for the feet. Although these were common in many parts of mainland Europe, they were still very rare in this country.

In 1760 a fire broke out which did considerable damage to the roof and to the organ. After the death of John Robinson in 1762, Henry Heron, possibly the best known organist and composer of St. Magnus, took up the post until his death in 1795. That year we find our earliest record of the stop-list, describing only three manuals, so one assumes the fourth manual was either lost in the 1760 restoration or during other work on the instrument in 1782.

Sadly, little of the original Jordan pipework survives and what there is among just four ranks of pipes on this main Great manual – on the Open Diapasons I, II, Principal and Twelfth. Except for a few stops added by Spurden Rutt in 1924, the rest of the pipework was essentially built in the Victorian era, mostly either by Brindley and Foster or William Hill and his son. The first addition was of the Cremona in 1831 by one Mr. Parsons. It was in 1831 that we first read that Parsons fitted a ‘stop to take off all pedal pipes’. The famous German composer Felix Mendelssohn is often credited with persuading English organists and builders to add pedals to during his visits to England. His first visit to London was only two years earlier, in 1829, so that might have persuaded St Magnus to add pedals to its organ. In 1851, the year of the Great Exhibition, Gray and Davison totally overhauled the organ and added a new pedalboard. Undoubtedly, they would have used their work at St. Magnus to promote their firm at the Great Exhibition.

Apparently, by 1879, the organ had fallen into a bad state of disrepair and so a committee was formed to invite tenders from five firms, including from the original builders of the organ. As the historian J. T. Lightwood described in his History of the Organ at St. Magnus, “Subsequent investigation disclosed, to the astonished Committee, the fact that the original builder, by name Jordan, had crossed the river of that name some hundred and fifty years previously, and so no further attempt was made to trace him”. The contract was given to Brindley and Foster. The next work followed in 1891 by William Hill’s son, Thomas.

The last major work done on the instrument was in 1924 by Spurden Rutt, although there had been fundraising years before for major work for the bicentenary of the instrument in 1912. Rutt added three more pedal stops and the three large reeds on the Swell. He also updated the technology of the action, in other words, the connection between the key and the pipe to pneumatic action. This was unfortunate timing for the very next year, 1925, electric action for organs was developed which would have proved far more reliable. No major work has been done to the instrument since, except in 1948 after bomb damage and after a fire in 1995. Consequently the organ was substantially restored (in 1997) by Hill, Norman & Beard. John Scott gave an inaugural recital on 20 May 1998 following the completion of that restoration.

Henry Heron (1738-95, organist 1762-95)

Heron was assistant organist to John Robinson by 1760 and his appointment to the post of organist was clearly a weighty matter as the parish records record “expenses at the Swan on the choice of an Organist £0-10-0” on 3 May 1762 and further “expenses at the Swan” of £1-4-3 on 7 May 1762. Heron published Ten voluntaries for the organ or harpsichord (not dated, but between 1760 and 1770) and Parish Music Corrected (1790), entered at Stationers’ Hall on 17 December 1790. Other compositions included a hymn tune Ewell and an anthem O sing unto the Lord. An Anthem, taken out of the Psalms, as it was perform’d by the Orphans of the Asylum, on the first of August 1784 being the day appointed for a general thanksgiving, for peace with America. He also wrote many songs for the various pleasure gardens, such as Vauxhall, Rannelagh and Marylebone. Heron was buried at St Magnus on 21 June 1795. On 23 June 1795 it was “Resolved that no charge for the ground or any other expense attending the funeral of Mr Henry Heron, the late Organist of this parish, deceased … be made to the executors of the said Mr Heron.”